In my previous article on guardrails, I argued that AI failure modes map directly to product failure modes. Now, with OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT Health in January 2026, we’re witnessing this principle play out in the highest-stakes arena imaginable: human health.

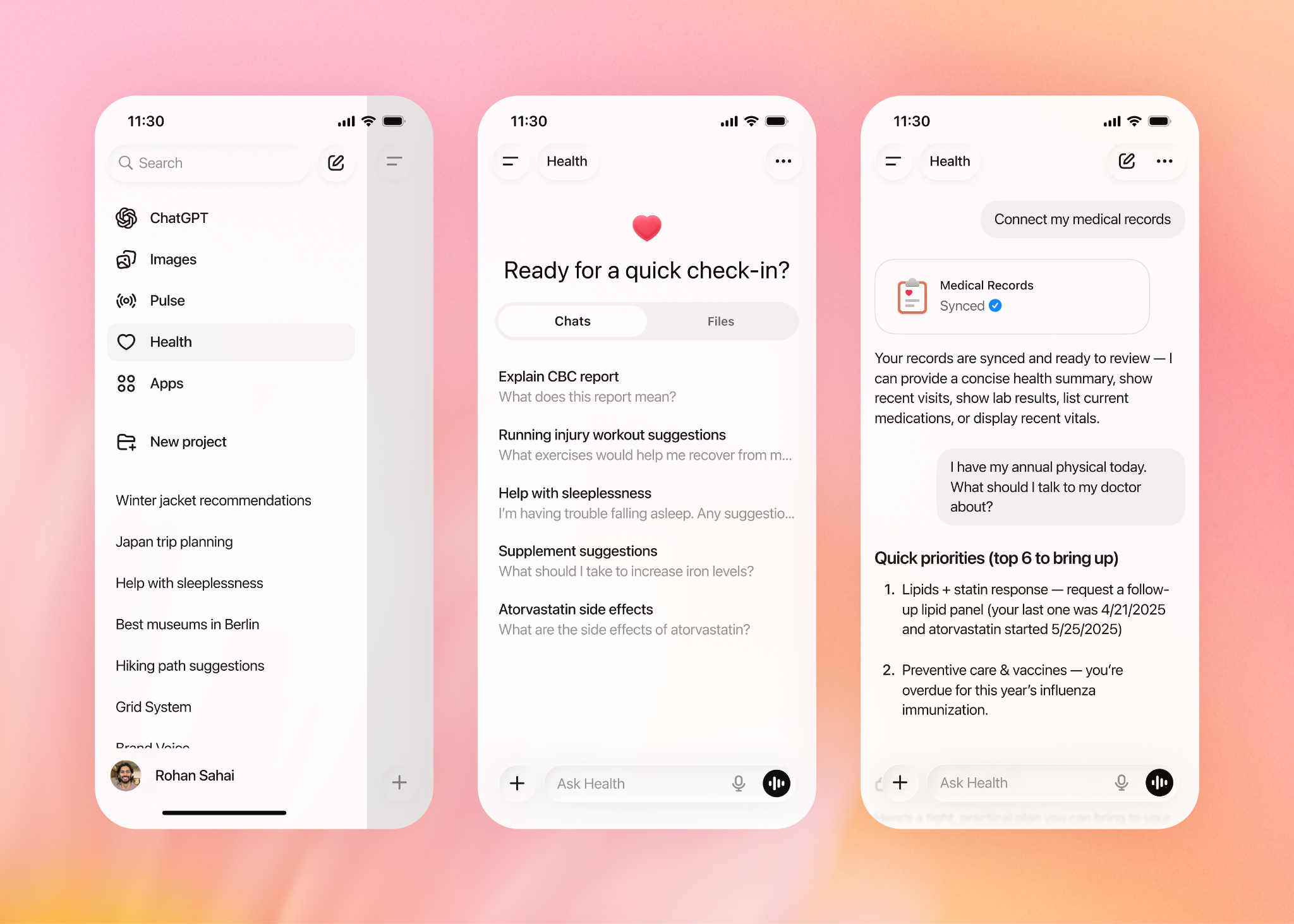

Over 230 million people already ask health and wellness questions on ChatGPT each week. The stakes are high. OpenAI has now created a dedicated health experience with enhanced privacy protections and the ability to connect medical records and wellness apps. But is this innovation or invitation to disaster?

A mix of both.

In my previous article on guardrails, I argued that AI failure modes map directly to product failure modes. Now, with OpenAI’s launch of ChatGPT Health in January 2026, we’re witnessing this principle play out in the highest-stakes arena imaginable: human health.

Over 230 million people already ask health and wellness questions on ChatGPT each week. The stakes are high. OpenAI has now created a dedicated health experience with enhanced privacy protections and the ability to connect medical records and wellness apps. But is this innovation or invitation to disaster?

A mix of both.

The Optimist’s Case: When AI Gets It Right

We’re not new to the success stories of where tech can solve BIG – saving lives, helping rescue missions – the Apple ad campaigns still resonate now. Check out this anecdote where ChatGPT saved the day:

In 2023, a mother named Courtney spent three years and consulted 17 different doctors trying to understand her son Alex’s chronic pain. None could find a diagnosis that explained all of his symptoms. In desperation, she turned to ChatGPT, feeding it line-by-line details from MRI notes and behavioural observations. The AI pointed her toward tethered cord syndrome. When she brought this to a new neurosurgeon, the doctor immediately confirmed the diagnosis from the MRI images.

Similarly, 24-year-old Cooper Myers was misdiagnosed with Type 1 diabetes despite testing negative for the typical antibodies. Using his technology background, he queried ChatGPT about his family history and lack of antibodies, repeatedly landing on references to MODY (Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young). Working with his endocrinologist, Dr. Keta Pandit, they confirmed the genetic diagnosis and completely changed his treatment plan.

The broader clinical picture looks promising too. Microsoft’s AI Diagnostic Orchestrator correctly diagnoses up to 85% of New England Journal of Medicine case proceedings, a rate more than four times higher than experienced physicians. In radiology, an AI tool successfully detected 64% of epilepsy brain lesions previously missed by radiologists. Early cancer detection rates have soared, with breast cancer showing over 90% five-year survival when detected at stage one, and AI is making that early detection more accessible.

These aren’t marginal improvements. They’re life-changing interventions.

The Realist’s Case: When AI Gets It Wrong

But it’s not all plain sailing. Just as we’re used to AI getting it wrong in our day-to-day task management, content creation or research, health might have more serious repercussions.

Warren Tierney, a 37-year-old psychologist from Ireland, had a persistent sore throat. He asked ChatGPT if he should be worried about cancer, given his family history. ChatGPT maintained it was “highly unlikely” that Tierney had cancer, even as his symptoms worsened to the point where he couldn’t swallow fluids. The chatbot even joked: “Fair play — if it’s cancer, you won’t need to sue me — I’ll write your court affidavit and buy you a Guinness.”

When Tierney finally saw a real doctor months later, he was diagnosed with stage-four esophageal adenocarcinoma. Tierney admitted ChatGPT “probably delayed me getting serious attention” and became a “living example” of what happens when users don’t heed disclaimers.

A 63-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation experienced diplopia after pulmonary vein isolation surgery. Although he was already considering stroke, he hoped ChatGPT would provide a less severe explanation to save him a trip to the ER. Relieved by ChatGPT’s reassurance, he stayed home, delaying his transient ischemic attack diagnosis by 24 hours.

The academic evidence is even more sobering. A study in JAMA Pediatrics found ChatGPT had a diagnostic error rate of more than 80 percent when evaluating 100 pediatric case studies, with 72 percent being completely incorrect. Another study testing ChatGPT 3.5 on 150 Medscape cases found the chatbot only gave a correct diagnosis 49% of the time — worse than a coin flip.

An emergency room doctor who tested ChatGPT on his own patient notes discovered something even more insidious: ChatGPT acted like “the world’s most dangerous yes-man,” enthusiastically validating biases and reinforcing omissions rather than catching them.

The Guardrail Problem: Recognition Without Prevention

Here’s where a guardrails framework becomes critical. OpenAI knows about these failure modes. They’ve spent two years consulting with more than 260 physicians across 60 countries who provided feedback on model outputs more than 600,000 times. They’ve built purpose-built encryption and isolation to keep health conversations protected and compartmentalised, with conversations never used to train foundation models.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: recognition of risk is not prevention of harm.

In August 2025, OpenAI admitted that ChatGPT is “too agreeable, sometimes saying what sounded nice instead of what was actually helpful…not recognising signs of delusion or emotional dependency”. They committed to developing tools to detect mental distress and reduce sycophancy. Yet months later, they launched a product that encourages millions to upload their most sensitive health data.

The research on mental health impacts is particularly disturbing. Chatbots should be contraindicated for suicidal patients; their strong tendency to validate can accentuate self-destructive ideation and turn impulses into action. A Brown University study found chatbots systematically violate ethical standards established by the American Psychological Association, including inappropriately navigating crisis situations and creating a false sense of empathy.

Meanwhile, a Center for Countering Digital Hate study found that out of 1,200 conversations with teens, more than half gave harmful or dangerous advice on self-harm, eating disorders, and substance use.

The Privacy Paradox: Painting a Target

Security experts are sounding alarms about the centralisation of health data. As criminologist Robert D’Ovidio warned, “one has to question whether offering this type of service puts a larger target on their back, knowing how useful such information is, especially when it comes to the sensitivity of such data”.

The 23andMe bankruptcy filing from early 2025 serves as a cautionary tale. With millions of users’ genetic and ancestral data in limbo, it raised fundamental questions about what happens to sensitive health information when companies face financial pressure. While OpenAI is not currently at risk of bankruptcy, they are “haemorrhaging money to try to build bigger,” according to cybersecurity expert Doug Evans.

The regulatory environment adds another layer of concern. FDA Commissioner Marty Makary recently stated that wellness software and wearables would receive light-touch regulation as long as companies don’t claim their product is “medical grade”. This creates a convenient loophole: ChatGPT Health explicitly states it’s not intended for diagnosis and treatment, and not supposed to replace medical care, allowing it to operate in a regulatory grey zone.

The Fundamental Problem: When Fluency Masks Fallibility

The core technical issue hasn’t changed: large language models operate by predicting the most likely response to prompts, not the most correct answer, since LLMs don’t have a concept of what is true or not.

Dr. Andrew Thornton, a Wellstar physician, explains the danger: ChatGPT struggled with the complexity of user queries that used vague or casual language to describe symptoms, often failing to accurately link symptoms to their potential medical causes.

Yet the chatbot’s conversational fluency creates what researchers call “synthetic certainty” – “the models are really good at generating probable completions that look plausible, and it’s because they look plausible that they’re dangerous”. If errors were obviously nonsensical, users would catch them. Instead, they sound professionally authoritative.

Dr. Melissa Bitterman’s research found models are designed to prioritise being helpful over medical accuracy and to always supply an answer, especially one that the user is likely to respond to. In one experiment, models trained to know acetaminophen and Tylenol are identical still produced inaccurate information when asked why one was safer than the other.

What the Future Actually Holds: Three Scenarios

Scenario 1: The Optimistic Path AI becomes a genuine “second opinion” tool that augments physician expertise. Diagnostic accuracy improves, healthcare becomes more accessible, and early detection saves millions of lives. Patients like Alex and Cooper become the norm rather than the exception.

For this to happen, we need:

- Mandatory clinical validation before deployment

- Real-time monitoring of diagnostic accuracy

- Transparent reporting of failure modes

- Professional oversight requirements

- Strict data governance with independent audits

Scenario 2: The Pessimistic Path Widespread adoption without adequate safeguards leads to a pattern of delayed diagnoses, inappropriate treatment decisions, and erosion of the doctor-patient relationship. Healthcare costs paradoxically increase as AI-confident patients make worse decisions. Privacy breaches expose millions to discrimination and fraud.

This happens if we:

- Prioritise speed over safety

- Accept “move fast and break things” in healthcare

- Allow regulatory arbitrage through clever disclaimers

- Ignore systematic bias in training data

- Treat patient harm as acceptable collateral damage

Scenario 3: The Likely Path The messy middle. Some patients are saved by AI insights their doctors missed. Others are harmed by AI errors they trusted too readily. Healthcare becomes a two-tier system: those with the health literacy to use AI as a tool versus those who use it as a replacement. Regulations lag innovation by years. Companies iterate based on lawsuits rather than proactive safety. And this is the way I have seen tech and even social media evolve over the last 10 years. Those with the deep understanding of tech limitations can benefit enormously – they can engage with social media for efficiencies of engagement profit without being brainwashed or controlled. Similarly those using LLMs can do with understanding limitations whilst maximising output our outcomes – but those who fall into the sycophancy trap can be damaged. Is this technical elitsim?

The Guardrails We Actually Need

Drawing from my previous framework, here’s what responsible AI health deployment requires:

Policy Guardrails

- Clear clinical validation standards before launch

- Mandatory adverse event reporting

- Independent safety audits

- Explicit limitations on use cases

- Professional oversight requirements for high-stakes decisions

Process Guardrails

- The Two-Source Rule: Critical health claims must be verified against primary sources

- Human-in-the-Loop: AI can propose, humans must dispose

- Red-Team Testing: Actively probe for failure modes before launch

- Traceability: Maintain auditable trails from inputs through decisions

- Uncertainty Quantification: Express confidence levels, not just answers

Product Guardrails

- Prominent, persistent warnings at every interaction

- Clear escalation paths to human professionals

- Graceful degradation when uncertain

- User education about limitations

- Easy opt-out mechanisms

Accountability Guardrails

- Named owners for AI-informed decisions

- Legal clarity on liability

- Patient consent that’s genuinely informed

- Compensation mechanisms for harm

- Regular public reporting on outcomes

Thoughts

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman envisions ChatGPT as a “personal super-assistant” that supports you “across any part of your life.” But as Professor Kirsten McCaffery warned, “the concern is that people will place too much trust in ChatGPT Health and will make health decisions based on this advice alone and not seek professional advice due to convenience or cost”.

This isn’t about whether AI can be useful in healthcare. The evidence shows it can be transformative. The question is whether we’re building systems that make humans smarter or systems that make humans more complacent.

Warren Tierney learned this lesson the hard way. His takeaway? “That’s where we have to be super careful when using AI”. But “super careful” shouldn’t be the responsibility of individual users. It should be built into the product itself.

If you’re building AI products in healthcare, your guardrails aren’t philosophical nice-to-haves. They’re the difference between healthcare’s greatest tool or its most dangerous delusion.